Since the beginning of time, humans have interacted with one another through language and forms of literature. Whether it be drawings on stone like ancient cuneiform, scripts marked by symbols that outline stories, or the pages of poetry and entries of new information that benefit the coming generations and carry on craftsmen from centuries ago.

Dating back to the eighth century, cursive emerged as a new style of penmanship. The graceful fall of a quill and ink detailed classic documents, and one of the most commonly known is the United States Constitution.

Authors and teachers began practicing this skill, and it grew as a globally taught art among schools for decades.

Although it seems like this beautiful technique dominated colonial times and writing, it has taken on a new reputation as “rare” and almost “lost” through the years. Modern-day schools require no conception or ability to write in cursive, but should it be a basic skill for Americans to know?

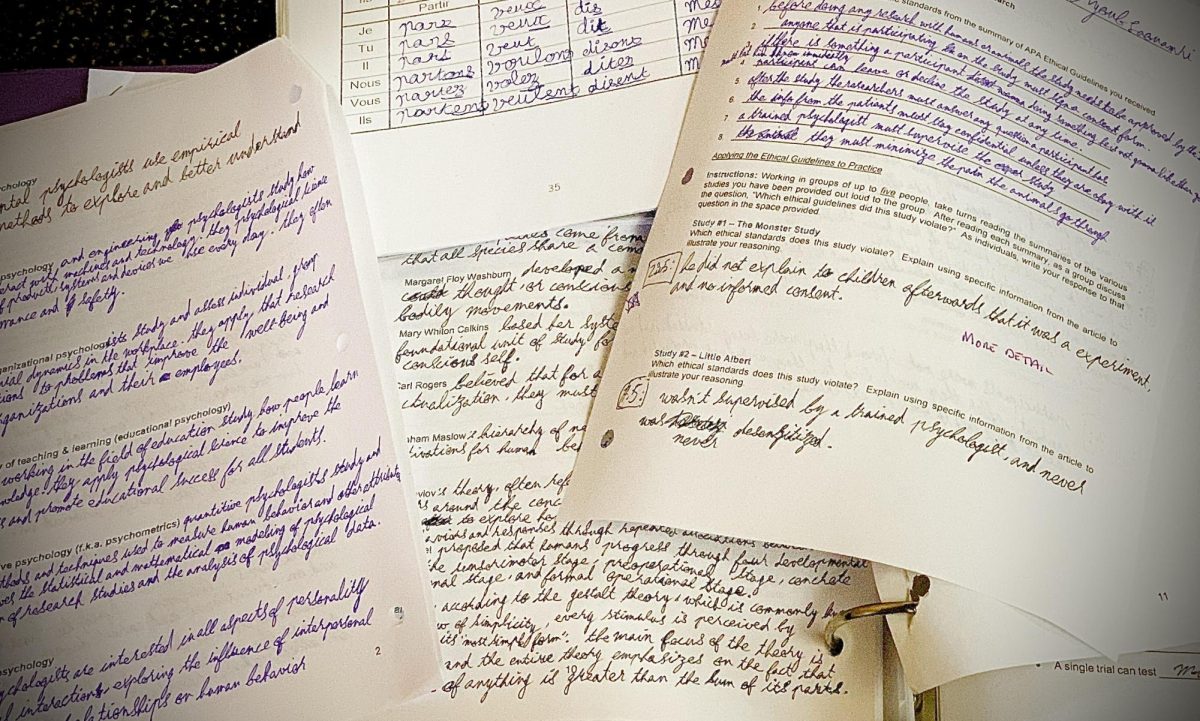

Sophomore Corentin Saad recalls, “I learned how to write cursive back in first grade when I lived in France. I had a notebook to practice and trace every letter in the alphabet in cursive, all in pen, because they didn’t like pencils. Mostly everyone in the United States writes in print.”

Shannon Doyne from the New York Times recognizes the possible downfall of society and the loss of history that would be sacrificed by the dismissal of cursive, “What happens when young people who are not familiar with cursive have to read historical documents?” Doyne’s perspective enlightens teachers and students on the critical importance of this art.

Students nationwide are still often taught cursive, but this learning stage typically happens at the elementary or middle school levels. Still, school districts continue to dismiss teaching handwriting and put this category of learning on the back burner.

Professor of education at Vanderbilt University, Steve Graham, remarks, “Far less time teaching handwriting in general than years ago.” Graham’s response alludes to the progressive movement towards cursive disappearing from school curriculums.

The worry is for student awareness and education of cursive writing and the need for this skill of reading and writing the style of print.

Another supporting response to this topic comes from sophomore Ayoub Laouamri, “With the increasing use of digital devices, many students are not being taught cursive writing as a standard part of their education.”

Teachers have been pouring into young students how to navigate Google platforms and develop exceptional typing accuracies rather than how students produce handwritten sentences.

Laouamri continues, “Even though digital skills are important, a well-rounded education can improve a student’s overall literacy and communication skills.”

Cursive may not seem prevalent, but the reality is that the world relies on cursive more than it realizes. When students become older, many important documents (taxes, checks, sign-offs, etc.) will require signatures, which are written in cursive. Most people can’t read cursive handwriting, let alone write their names in cursive.

Although to some, cursive appears incomprehensible and almost ‘cryptic,’ other people experience this to be the only form of writing that they can legibly write.

European countries are known for their consideration and use of cursive. The Roman alphabet has since evolved into many textile fonts and variations of letters. Some people believe, though, that connection to archival material is lost when students turn away from cursive.

Teachers barely talk about cursive anymore. As a form of calligraphy, cursive should be known as a form of artistic expression and offered to students who want to learn this form of penmanship.

Cursive lettering used to be second nature, but the practice has been lost. Students should have the resources to learn cursive in school and should be applauded for their beautiful handwriting.